PubMed Central, CAS, DOAJ, KCI

Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Yeungnam Med Sci > Volume 38(3); 2021 > Article

-

Case report

Successful laparoscopic surgery of accessory cavitated uterine mass in young women with severe dysmenorrhea -

Joon Cheol Park1

, Dong Ja Kim2

, Dong Ja Kim2

-

Yeungnam University Journal of Medicine 2021;38(3):235-239.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.12701/yujm.2020.00696

Published online: September 18, 2020

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

2Department of Forensic Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- Corresponding author: Dong Ja Kim, MD, PhD Department of Forensic Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, 680 Gukchaebosang-ro, Jung-gu, Daegu 41944, Korea Tel: +82-53-420-4889 Fax: +82-53-422-4712 E-mail: dongja222@knu.ac.kr

Copyright © 2021 Yeungnam University College of Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 6,167 Views

- 160 Download

- 4 Crossref

Abstract

- Accessory cavitated uterine mass (ACUM) is a rare and unique condition seen in young women. We report cases of ACUMs in two patients, a 14-year-old girl and a 25-year-old woman, both with complaints of severe dysmenorrhea that had started at menarche and had progressively worsened since. A large cystic lesion was localized in the anterolateral wall of the myometrium separate from the endometrium, which was difficult to distinguish from congenital uterine anomalies. Laparoscopic excision of the ACUMs was successful and completely resolved the dysmenorrhea. Early investigation of severe dysmenorrhea in young women can provide appropriate management and relieve symptoms.

- Severe dysmenorrhea in young women is usually primary dysmenorrhea, but cases with poor response to medical treatment may be due to endometriosis, adenomyosis, or Müllerian duct anomaly [1]. Juvenile cystic adenomyoma is a rare variant of adenomyosis characterized by the presence of a large hemorrhagic cyst resulting from extensive menstrual bleeding in ectopic endometrial glands [2]. Especially in young women, it can present as a focal cystic mass with severe dysmenorrhea, abdominal cramps, and pelvic pain resistant to medical treatment [3]. Currently, this unique entity has been renamed as accessory cavitated uterine mass (ACUM) [4]. ACUM is suggested to be a new variety of Müllerian anomaly that is usually located at the level of the insertion of the round ligament and is related to dysfunction of the female gubernaculum [4]. Therefore, ACUM closely mimics the unicornuate uterus with obstructed cavitated rudimentary horn, and differential diagnosis might not be easy even with the use of pelvic ultrasonography, hysterosalpingography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [5]. Confirmation of both ostia using hysteroscopy can be helpful in making an accurate diagnosis. Herein, we report two cases of successful laparoscopic mass excision in young women who complained of severe dysmenorrhea, diagnosed as ACUM, with a brief review of the literature.

Introduction

- 1. Case 1

- A 14-year-old girl complained of severe dysmenorrhea that had developed and progressively worsened since menarche at age 12 years. She experienced lower abdominal pain for more than 10 days around her menstrual period, along with nausea and vomiting. She had taken oral analgesics during these periods; however, they did not relieve the pain. She had to visit the emergency room and miss school several times. Her body weight was 47 kg, and her height was 157 cm. Physical examination revealed diffuse tenderness of the lower abdomen and bimanual pelvic examination was not performed because she was a virgin. Laboratory tests were all within normal limits.

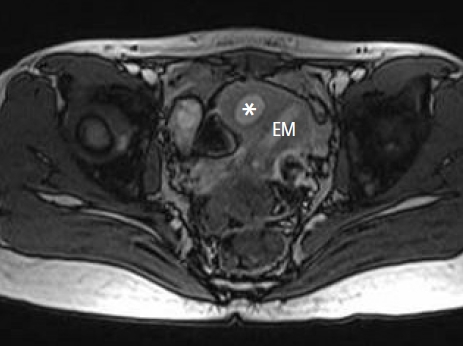

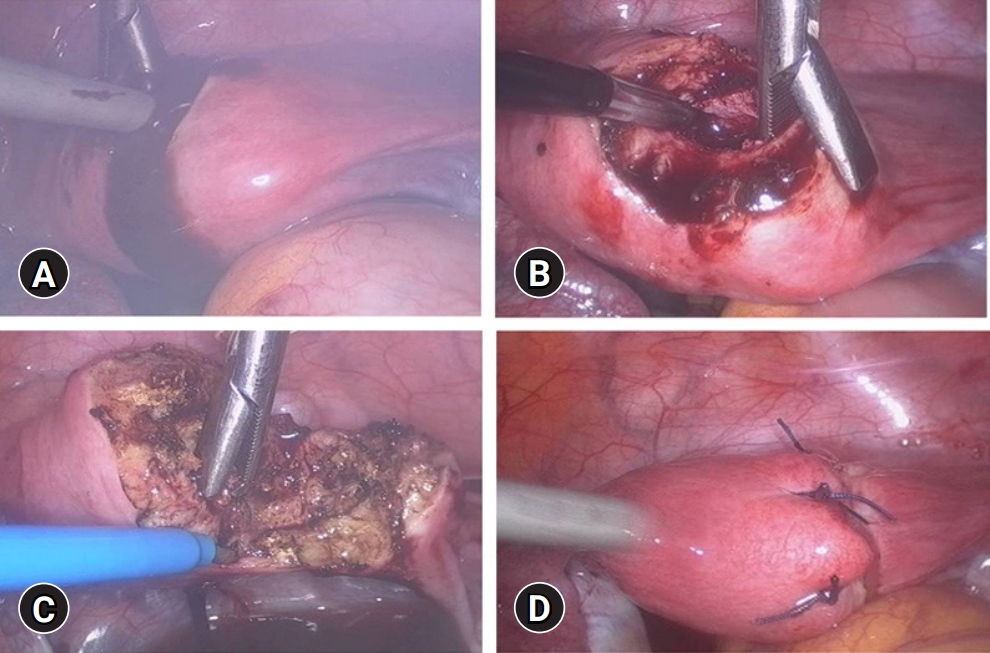

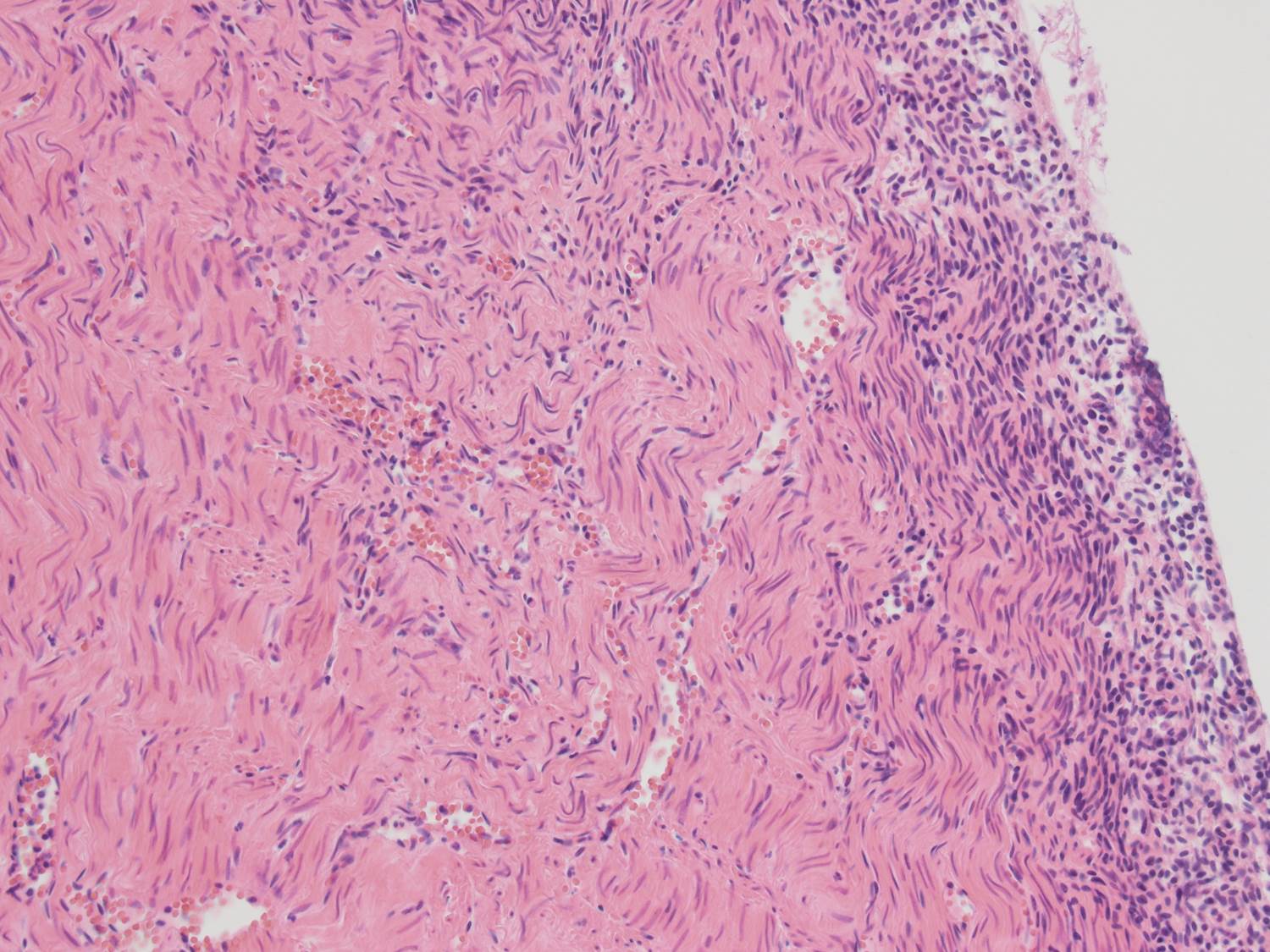

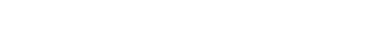

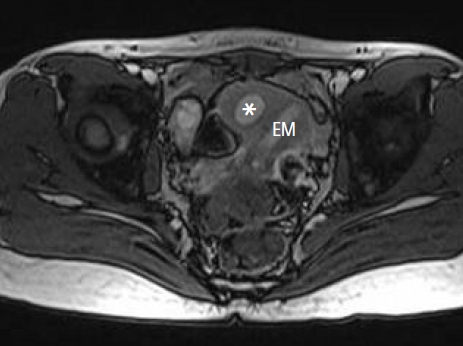

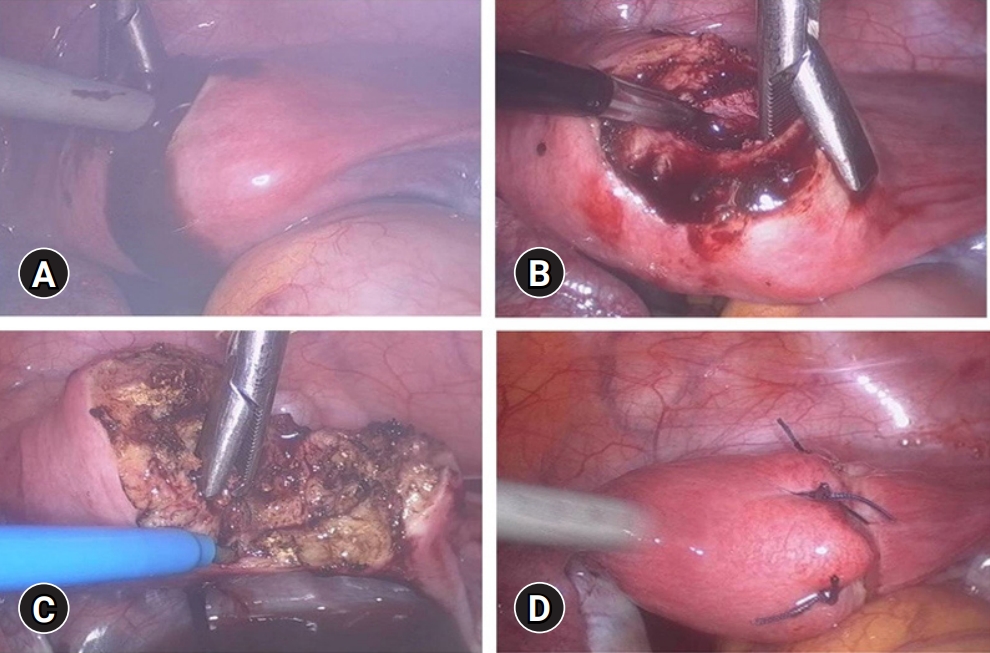

- Transrectal ultrasound revealed a 3-cm hyperechogenic mass on the right side of the uterus that was independent of the normal endometrium and ovaries. Pelvic MRI revealed a fluid collection in the right horn of the uterus. The preoperative MRI showed a bicornuate uterus with a noncommunicating horn (Fig. 1). After obtaining written consent, hysteroscopy was performed under general anesthesia, demonstrating a normal uterine cavity and bilateral ostia. Under general anesthesia with a muscle relaxant was used to avoid hymenal damage. Laparoscopy revealed a mass bulging out in the right anterior wall of the uterus. The myometrial wall over the cystic lesion was opened with monopolar scissors, and chocolate-like fluid was expelled from the cyst. The endometrial and myometrial tissue surrounding the cyst were completely resected using the monopolar hook. The myometrial defect was sutured by V-loc (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) in two layers and reinforced interruptedly with 0-Polysorb Vicryl (Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany) (Fig. 2). The abdominal cavity was thoroughly irrigated with saline, and the uterine wound was covered with Seperafilm (Genzyme Biosurgery, Framingham, MA, USA). The total operating time was 125 minutes, and the estimated blood loss was about 50 mL. Pathological examination showed a cyst wall lined with endometrial glandular epithelium and stromal cells surrounded by myometrium (Fig. 3). The postoperative period was uneventful. She was discharged 4 days after the operation. Her abdominal pain was completely resolved after surgery. She has had regular menstruation without complaints for 2 years after surgery.

- 2. Case 2

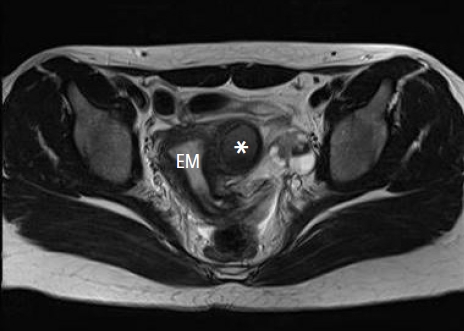

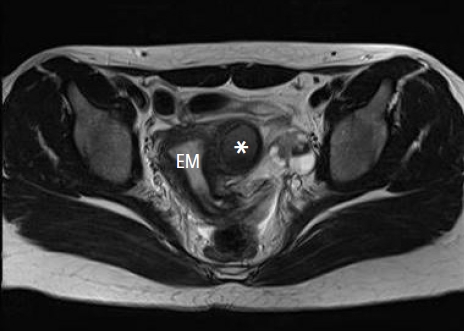

- A 25-year-old nulligravida visited the emergency room with severe abdominal pain in the left lower quadrant. The urologist examined her first and ruled out the possibility of renal stones or other urological disorders. She had a history of erratic severe lower abdominal pain refractory to medical treatment. She showed a tender abdomen without rebound tenderness or costovertebral tenderness. Pelvic ultrasound revealed a 3-cm hypoechogenic mass on the left side of the uterus, which did not communicate with the endometrial cavity. The presumptive diagnosis of pelvic MRI was a unicornuate uterus with a rudimentary horn containing hemorrhage (Fig. 4). However, in the operative field, a smooth protruding mass was found on the left anterior wall of the uterus, with both ovaries and tubes grossly intact. We also ruled out unicornuate uterus by confirming that the uterine cavity and ostia were normal, using hysteroscopy. Laparoscopic mass excision was performed. On pathological examination, the cyst wall was lined with endometrial glandular epithelium and stromal cells. In the surrounding myometrium, no other adenomyotic lesion was found (Fig. 5). The postoperative period was uneventful. Until now, she has not complained of dysmenorrhea or abdominal pain after surgery.

Cases

- The typical feature of juvenile cystic adenomyoma or ACUM is early-onset severe dysmenorrhea, which usually starts soon after menarche and is refractory to medical treatments [6]. ACUM was first described by Acién et al. [4] in 2010 and was described as juvenile cystic adenomyosis [6,7]. The diagnostic criteria for ACUM are as follows: (1) an isolated accessory cavitated mass; (2) a normal uterus (endometrial lumen), fallopian tubes, and ovaries; (3) surgical evidence with an excised mass and pathological findings; (4) an accessory cavity lined with endometrial epithelium with glands and stroma; (5) chocolate-brown colored fluid content; and (6) no adenomyosis (if the uterus has been removed), although there could be small foci of adenomyosis in the myometrium adjacent to the accessory cavity [4].

- Severe dysmenorrhea accompanied by a uterine mass usually suggests adenomyosis. Even though adenomyosis is usually a diffuse solid mass and develops in women in their forties, it can present as an adenomyoma, adenomyomatous polyps, and cystic adenomyomas [8]. Small cystic spaces, less than 0.5 cm in diameter, may be associated with adenomyosis. However, large adenomyotic cysts, referred to as cystic adenomyomas, are rare [9]. Juvenile cystic adenomyoma is defined as a solitary myometrial cyst measuring ≥1 cm, which is surrounded by hypertrophic endometrium, independent of the uterine lumen, and is present in women less than 30 years of age, in association with severe dysmenorrhea [10]. It is not common in late teenage. However, the youngest case known was a 13-year-old girl [11], and the case in the present study was 14 years old, only 2 years post menarche. To our knowledge, fewer than 40 cases, worldwide, have been reported in the literature [10,12,13]. We agree that most juvenile cystic adenomyomas might, in fact, be ACUMs because they present with similar clinical and histopathological characteristics [4]. When this lesion is considered a variant of adenomyosis, surgeons have to focus on en bloc resection with sufficient margins to reduce the risk of residual adenomyotic lesions in the surrounding myometrium. However, when it is considered a variant Müllerian anomaly, we can expect symptomatic relief only after the endometrial lesion of the cyst wall is eliminated. In our case, the surrounding myometrium did not contain adenomyotic lesions. The patients had complete symptomatic relief after resection of the endometrial lesion lining the cyst wall. However, the pathophysiology of this lesion still remains unclear and needs further study.

- Cystic adenomyomas or ACUMs are mostly located in the lateral wall near the uterine round ligament attachment site. They mimic uterine anomalies such as a unicornuate uterus with a rudimentary horn, bicornuate uterus with a noncommunicating horn, and hematometra in uterine didelphys with a transvaginal septum. Additionally, the degenerated myoma and vesicouterine endometrioma are also considered as differential diagnoses [12]. ACUM is a cystic lesion that is independent of the normal endometrium, whereas hematometra and hematocolpos are present in the obstructing Müllerian anomaly [10]. Even with MRI, it can sometimes be difficult to differentiate it from a cavitated noncommunicating rudimentary uterine horn. In this situation, hysterosalpingography and hysteroscopy can be useful in distinguishing it from a uterine anomaly [5]. In our case, the patients were young and complained of unbearable severe dysmenorrhea that developed and progressively worsened from menarche. Therefore, obstructive Müllerian anomaly was first considered, and the interpretation of preoperative MRI was also a uterine anomaly with a noncommunicating horn. However, hysteroscopy showing a normal uterine cavity and ostia were helpful in making the differential diagnosis.

- On pathological examination, ACUM is characterized by ectopic endometrial epithelium, glands, and/or stroma within the myometrium. A well-demarcated region of myometrial hyperplasia borders the endometrial tissue and appears as a thick-walled, well-circumscribed lesion within the uterine muscle [14,15].

- Initial empirical treatment, including oral contraceptives and analgesia, can be attempted. However, ACUM is usually resistant to medical treatment, and surgical removal might be unavoidable. Laparoscopic excision has been attempted and has shown good postoperative results, comparable to those of exploratory laparotomy [10]. Other surgical approaches have been proposed, such as radiofrequency ablation under ultrasonography guidance [16], single incision with monopolar cautery [17], or the use of robotic surgery [18].

- In the cases presented, ACUM was diagnosed in a 14-year-old adolescent girl and a 25-year-old young woman, both presenting with complaints of unbearable severe dysmenorrhea. Laparoscopic mass excision successfully resolved the dysmenorrhea. Early investigation of severe dysmenorrhea in young women can help with appropriate management and reduce the duration of symptoms.

Discussion

-

Ethical statements

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center (IRB No: 2020-08-010). Written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

-

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, and Investigation: JCP, DJK; Data curation, Resources, and Software: JCP; Supervision and Validation: DJK; Writing-original draft: JCP; Writing-review & editing: DJK.

Notes

- 1. Bedaiwy MA, Henry DN, Elguero S, Pickett S, Greenfield M. Accessory and cavitated uterine mass with functional endometrium in an adolescent: diagnosis and laparoscopic excision technique. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013;26:e89–91.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Tamai K, Koyama T, Umeoka S, Saga T, Fujii S, Togashi K. Spectrum of MR features in adenomyosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2006;20:583–602.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Nabeshima H, Murakami T, Nishimoto M, Sugawara N, Sato N. Successful total laparoscopic cystic adenomyomectomy after unsuccessful open surgery using transtrocar ultrasonographic guiding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2008;15:227–30.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Acién P, Acién M, Fernández F, José Mayol M, Aranda I. The cavitated accessory uterine mass: a Müllerian anomaly in women with an otherwise normal uterus. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1101–9.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Jain N, Verma R. Imaging diagnosis of accessory and cavitated uterine mass, a rare mullerian anomaly. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2014;24:178–81.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Paul PG, Chopade G, Das T, Dhivya N, Patil S, Thomas M. Accessory cavitated uterine mass: a rare cause of severe dysmenorrhea in young women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015;22:1300–3.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Takeda A, Sakai K, Mitsui T, Nakamura H. Laparoscopic management of juvenile cystic adenomyoma of the uterus: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2007;14:370–4.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Brosens I, Gordts S, Habiba M, Benagiano G. Uterine cystic adenomyosis: a disease of younger women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2015;28:420–6.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Nabeshima H, Murakami T, Terada Y, Noda T, Yaegashi N, Okamura K. Total laparoscopic surgery of cystic adenomyoma under hydroultrasonographic monitoring. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2003;10:195–9.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Takeuchi H, Kitade M, Kikuchi I, Kumakiri J, Kuroda K, Jinushi M. Diagnosis, laparoscopic management, and histopathologic findings of juvenile cystic adenomyoma: a review of nine cases. Fertil Steril 2010;94:862–8.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Fisseha S, Smith YR, Kumetz LM, Mueller GC, Hussain H, Quint EH. Cystic myometrial lesion in the uterus of an adolescent girl. Fertil Steril 2006;86:716–8.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Pontrelli G, Bounous VE, Scarperi S, Minelli L, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Florio P. Rare case of giant cystic adenomyoma mimicking a uterine malformation, diagnosed and treated by hysteroscopy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:1300–4.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Kim MJ. A case of cystic adenomyoma of the uterus after complete abortion without transcervical curettage. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2014;57:176–9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Tahlan A, Nanda A, Mohan H. Uterine adenomyoma: a clinicopathologic review of 26 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006;25:361–5.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Ho ML, Ratts V, Merritt D. Adenomyotic cyst in an adolescent girl. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2009;22:e33–8.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Ryo E, Takeshita S, Shiba M, Ayabe T. Radiofrequency ablation for cystic adenomyosis: a case report. J Reprod Med 2006;51:427–30.PubMed

- 17. Kumakiri J, Kikuchi I, Sogawa Y, Jinushi M, Aoki Y, Kitade M, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery using an articulating monopolar for juvenile cystic adenomyoma. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2013;22:312–5.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Akar ME, Leezer KH, Yalcinkaya TM. Robot-assisted laparoscopic management of a case with juvenile cystic adenomyoma. Fertil Steril 2010;94:e55–6.ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Accessory and cavitated uterine masses: a case series and review of the literature

S. Dekkiche, E. Dubruc, M. Kanbar, A. Feki, M. Mueller, J-Y. Meuwly, P. Mathevet

Frontiers in Reproductive Health.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Accessory cavitated uterine malformation: Enhancing awareness about this unexplored perpetrator of dysmenorrhea

Rana Mondal, Priya Bhave

International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics.2023; 162(2): 409. CrossRef - Large uterine juvenile cystic adenomyoma in an adolescent

Zlatan Zvizdic, Irmina Sefic-Pasic, Nermina Ibisevic, Senad Murtezic, Semir Vranic

Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports.2022; 81: 102258. CrossRef - Laparoscopic Approach to Accessory and Cavitatory Uterine Mass(ACUM): A Report of Four Patients in a Year

Kavitha Yogini Duraisamy, S. Saidarshini, Devi Balasubramaniam, Pradeepa, Divya Gnanasekaran

The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India.2022; 72(S2): 466. CrossRef

E-Submission

E-Submission Yeungnam University College of Medicine

Yeungnam University College of Medicine PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite