Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with recurrent Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease

Article information

Abstract

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD), also known as histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, is a self-limiting lymphadenitis. It is a benign disease mainly characterized by high fever, lymph node swelling, and leukopenia. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening disease with clinical symptoms similar to those of KFD, but it requires a significantly more aggressive treatment. A 19-year-old Korean male patient was hospitalized for fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. Variable-sized lymph node enlargements with slightly necrotic lesions were detected on computed tomography. Biopsy specimen from a cervical lymph node showed necrotizing lymphadenitis with HLH. Bone marrow aspiration showed hemophagocytic histiocytosis. The clinical symptoms and the results of the laboratory test and bone marrow aspiration met the diagnostic criteria for HLH. The patient was diagnosed with macrophage activation syndrome—HLH, a secondary HLH associated with KFD. He was treated with dexamethasone (10 mg/m2/day) without immunosuppressive therapy or etoposide-based chemotherapy. The fever disappeared within a day, and other symptoms such as lymphadenopathy, ascites, and pleural effusion improved. Dexamethasone was reduced from day 2 of hospitalization and was tapered over 8 weeks. The patient was discharged on day 6 with continuation of dexamethasone. The patient had no recurrence at the 18-month follow-up.

Introduction

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD), also known as histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, is a self-limiting lymphadenitis. Its symptoms mainly include high fever, lymph node swelling, and leukopenia [1]. The etiology of KFD is unclear, and KFD is presumed to be preceded by infectious or autoimmune diseases, although this has not been confirmed [2]. Treatment is symptomatic with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and most symptoms improve within a few months [2]. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening disease with clinical symptoms similar to those of KFS. Severe systemic hyperinflammation requires a markedly more aggressive treatment than that required for KFD. Only a few cases have been reported for both diseases. We herein report a case of HLH associated with KFD in a 19-year-old male patient who was admitted with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy and was successfully treated with corticosteroids.

Case

A 19-year-old male patient presented with high fever and neck swelling for 5 weeks. The patient was treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate, ceftriaxone, and dexamethasone (5 mg/day) for 9 days at the local medical center (LMC), but his condition did not improve. The patient had experienced KFD 3 years earlier with symptoms such as fever, cervical lymphadenitis, and joint pain. In the laboratory tests, no specific findings, except elevation in the C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), were noted. Lymph node enlargement and slightly necrotic lesions were observed in the neck computed tomography (CT) scan. Analysis of the core needle biopsy specimen indicated histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, which was observed in KFD. The patient had a steroid dependency and was treated with hydroxychloroquine [3].

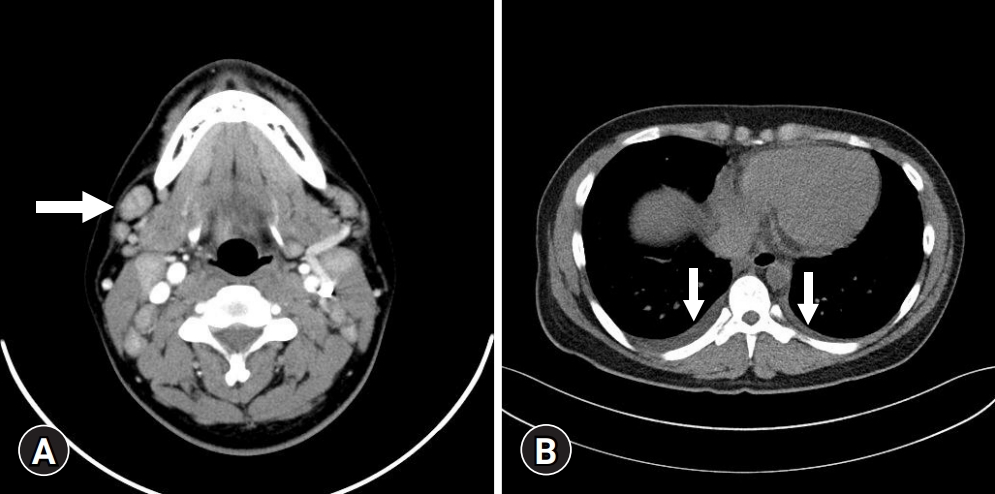

Physical examination revealed painful cervical lymph node enlargement and tonsillar swelling on both sides. Variable-sized lymph node enlargements with slightly necrotic lesions were detected on CT (Fig. 1A). A small amount of bilateral pleural effusion and multiple infiltrative enlarged lymph nodes in the anterior mediastinum were observed (Fig. 1B). Mild hepatomegaly and segmental wall thickening of the gallbladder were also noted.

(A) Neck computed tomography (CT) shows scattered, variable-sized lymph node enlargements (arrow) on both neck at levels Ⅰ to Ⅳ. (B) Chest CT shows a small amount of bilateral pleural effusion (arrows).

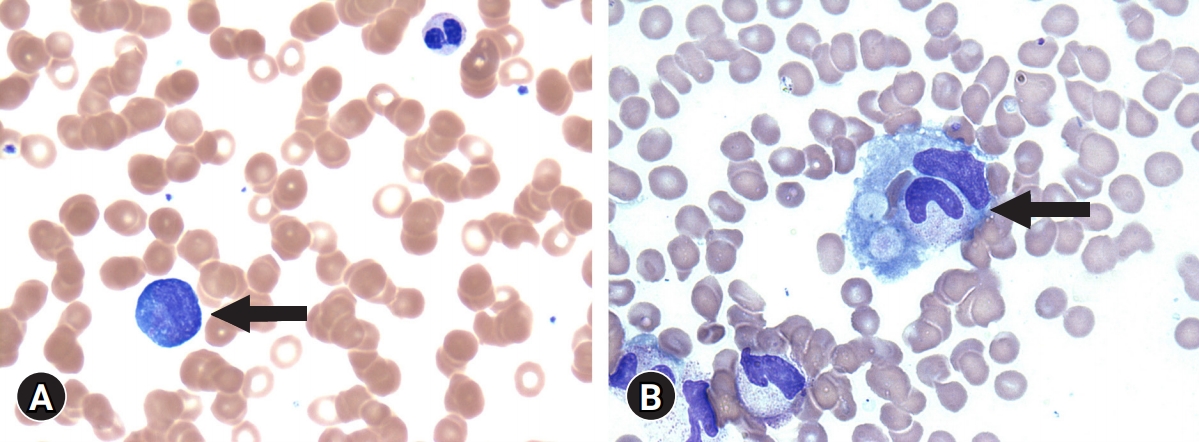

Laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cell count, 2,060/μL (54.9% neutrophils); absolute neutrophil count, 1,130/μL; hemoglobin level, 11.8 g/dL; platelet count, 145,000/μL; aspartate aminotransferase, 275 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 164 IU/L; and γ-glutamyl transferase, 916 IU/L. Other laboratory findings were as follows: elevated CRP level, 7.417 mg/dL (range, <0.5 mg/dL); ESR, 32 mm/hr (range, 0–20 mm/hr); elevated procalcitonin level, 16.2 ng/mL (range, 0–0.5 ng/mL); elevated serum ferritin level, 19,640.61 ng/mL (range, 29–278 ng/mL); elevated fasting triglyceride level, 372 mg/dL (range, 35–160 mg/dL); fibrinogen level, 229 mg/dL (range, 200–400 mg/dL); elevated soluble CD25 (sIL-2 receptor) level, 2,817 U/mL (range, 158–623 U/mL); natural killer cell activity, >2,000 pg/mL (range, >500 pg/mL); C3 level, 99.6 mg/dL (range, 83–177 mg/dL); C4 level, 43.6 mg/dL (range, 15–45 mg/dL); CH50 level, 55 U/mL (range, 75–160 U/mL); antinuclear antibody, negative; cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin (Ig) M, negative; and Epstein-Barr virus IgM and polymerase chain reaction, negative. He was initially treated with vancomycin, meropenem, and metronidazole. However, he did not respond to antibiotic treatment, and the fever persisted. Core needle biopsy specimen from the cervical lymph node and bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed on hospitalization day 3. The cervical lymph node biopsy showed necrotizing lymphadenitis with HLH (Fig. 2). Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy showed normocellular marrow with increased hemophagocytic histiocytosis (Fig. 3). The patient met the five diagnostic criteria for HLH. Thus, he was diagnosed with secondary HLH associated with KFD.

Histological findings of the cervical lymph node. The biopsy specimen shows necrotizing lymphadenitis with karyorrhectic nuclear debris (arrows) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×400).

(A) Peripheral blood smear shows atypical lymphocytes (arrow) (Wright’s stain, ×1,000). (B) Bone marrow aspirate smear shows hemophagocytic histiocytes (arrow) engulfing granulocytes and red blood cells (Wright’s stain, ×1,000).

The patient initiated treatment with intravenous dexamethasone (10 mg/m2/day). The fever disappeared in a day, and other symptoms such as lymphadenopathy, ascites, and pleural effusion improved. Dexamethasone was reduced from day 2 and was tapered over 8 weeks. The patient was discharged on day 6 with continuation of dexamethasone. He was followed up at the outpatient clinic and had no recurrence at the 18-month follow-up. Next-generation sequencing was performed to determine any genetic abnormalities related to HLH, but no such abnormalities were found.

Discussion

KFD is a benign disease mainly characterized by high fever, lymph node swelling, and leukopenia. It usually develops in young adults aged less than 30 years and is confirmed by biopsy with histological findings of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis [1]. KFD usually requires no special treatment. However, when systemic symptoms are severe or accompanied by an autoimmune disease, steroid treatment should be considered [1].

HLH is a syndrome that manifests in patients with severe systemic hyperinflammation. The typical findings of HLH include fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenia. Other common findings include hypertriglyceridemia, coagulopathy with hypofibrinogenemia, liver dysfunction, and elevated levels of ferritin and serum transaminases. Other, less common, initial clinical findings include lymphadenopathy, skin rash, jaundice, and edema. Primary HLH occurs because of a genetic abnormality or is idiopathic, but secondary HLH is known to be caused by strong activation of the immune system, in most cases, because of severe infections and is mainly caused by immunosuppression. However, it can also occur in malignancy and rheumatologic conditions [4]. HLH has early symptoms similar to KFD but requires active treatment and has a poor prognosis.

We report a case of secondary HLH caused by recurrent KFD. Until now, fewer than 20 cases of HLH with KFD have been reported (Table 1) [5-18]. According to the literature review, the average age of patients was 17.5±11.6 years, and this disease affected 12 male patients (63.2%) and seven female patients (36.8%). The incidence rates by country were as follows: Korea, 47.4% (n=9); Japan, 15.8% (n=3); Taiwan, 15.8% (n=3); United Kingdom, 5.3% (n=1); United States, 5.3% (n=1); Qatar, 5.3% (n=1); and Thailand, 5.3% (n=1). In terms of race, 18 out of 19 patients were Asian, accounting for 94.7% of patients. The most common symptoms were fever (100%) and lymphadenopathy (89.5%), followed by seizure, fatigue, and erythema. The medications administered in the reports were steroid (68.4%), intravenous Ig (36.8%), etoposide (21.1%), and cyclosporine A (10.5%). In terms of outcomes, 17 of the patients (89.5%) had complete remission, whereas two patients (10.5%) died. HLH with KFD has a relatively good prognosis and response to treatment, but its diagnosis and standard treatment have not yet been established.

Clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcome of Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

The manifestation of HLH symptoms in patients with rheumatic conditions is called macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). From the revised classification in 2016, the term MAS-HLH has been suggested. Among patients with secondary HLH, those with associated rheumatic conditions are diagnosed with MAS-HLH [19]. In our case, the patient was diagnosed with HLH caused by KFD. As KFD is associated with rheumatic disease [2], HLH associated with KFD was regarded as MAS-HLH. Currently, the standard therapy for HLH comprises dexamethasone and etoposide based on HLH-94 treatment protocol. The treatment of HLH should be accompanied by appropriate treatment of the identified underlying trigger [4]. Although the HLH-94 protocol is required in most HLH patients, steroids with or without intravenous Ig may be sufficient for patients with less severe HLH or those with MAS-HLH [20]. Cases of successful treatment by steroid alone have been reported [8,10,16,18]. Our patient did not appear seriously ill, and the dose of steroid therapy at the LMC was inadequate. Therefore, we decided to administer an appropriate dose of steroid alone. He was followed up at the outpatient clinic and presented with no recurrence at the 18-month follow-up. MAS-HLH is an autoimmune disease associated with rheumatic conditions. Therefore, steroid treatment was considered appropriate as the underlying triggers were eliminated with steroid administration. In this case, we confirmed the effectiveness of steroid treatment alone for MAS-HLH. Therefore, it would be appropriate to classify secondary HLH associated with KFD as MAS-HLH and to treat it accordingly.

In conclusion, recurrent KFD has the possibility of progressing to HLH. HLH requires a more aggressive treatment than KFD. However, in the case of MAS-HLH, specifically KFD-associated HLH, treatment with steroids alone should be provided without the administration of immunosuppressive drugs such as etoposide or cyclosporine A.

Notes

Ethical statements

This report was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Yeungnam University Hospital (IRB No: YUMC 2020-07-038). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This work was supported by the 2019 Yeungnam University Research Grant (219A480007).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: all authors; Data curation: SML, YTL, KMJ, MJG, JHL; Formal analysis and Supervision: JML; Funding acquisition and Validation: JML; Methodology: SML, YTL, KMJ, MJG, JHL; Investigation: SML; Resources: YTL, KMJ, MJG, JHL; Writing-original draft: all authors; Writing-review & editing: all authors.